Know the Formats

Posted: 2025-05-24 · Last updated: 2025-09-26 · Permalink

How can we harness groups to make effective, good decisions? We can think of many group decisions as being differentiated on two dimensions: how complex the decision is and how aligned the interests of group members are.

To say anything meaningful at all about this topic, it is necessary to stay quite general and vague. For example, what does it even mean for a decision to be “effective” or “good”? You are free to replace these words with the long-term satisfaction of all group members. I will come to examples below.

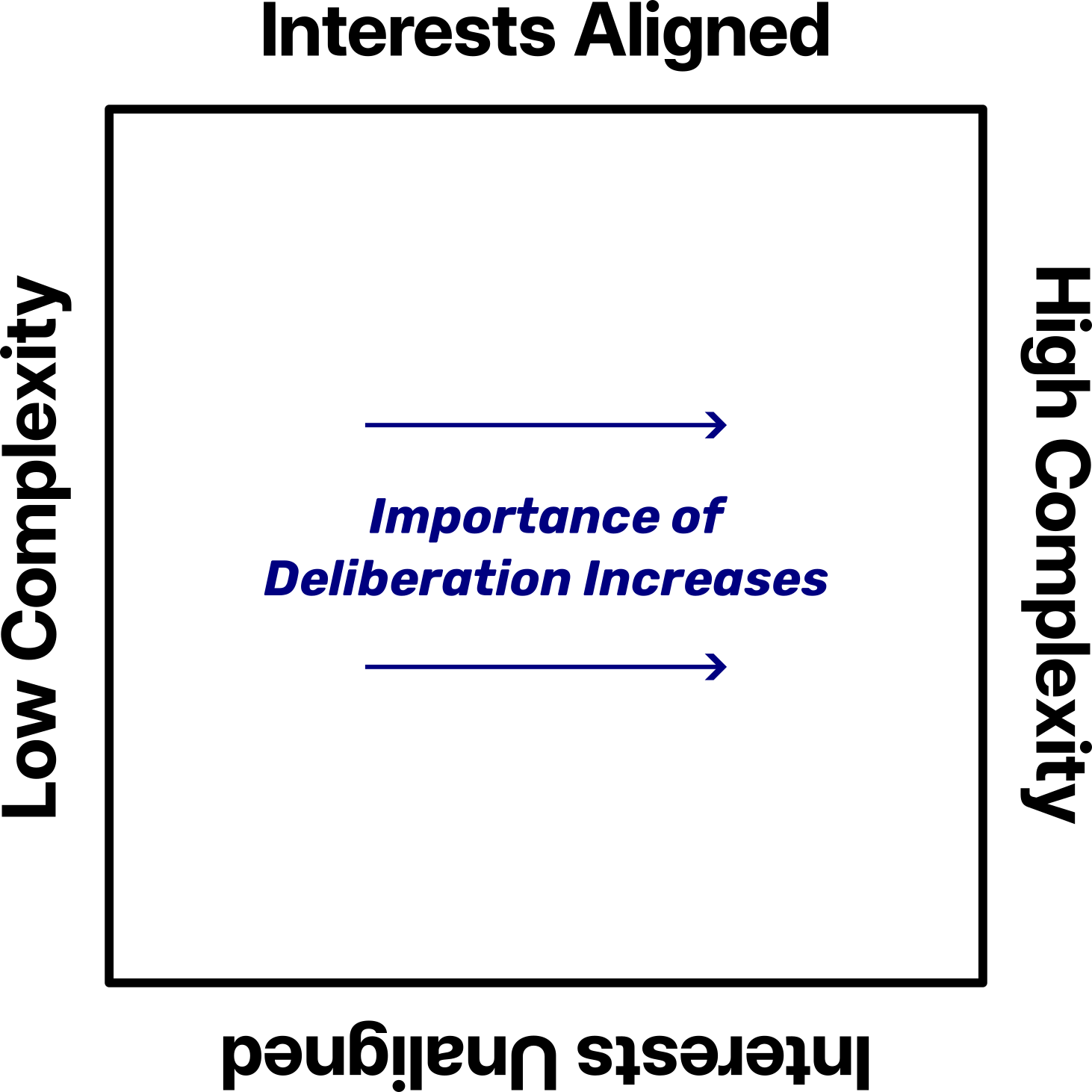

Decisions that involve fewer moving parts or that are simpler or easier to verify obviously require less time to think. When it comes to groups, there is also less need for discussions or what is sometimes called “deliberation.” On the other hand, complex topics need to be thoroughly talked through, subdivided, inspected, and finally once again put together.

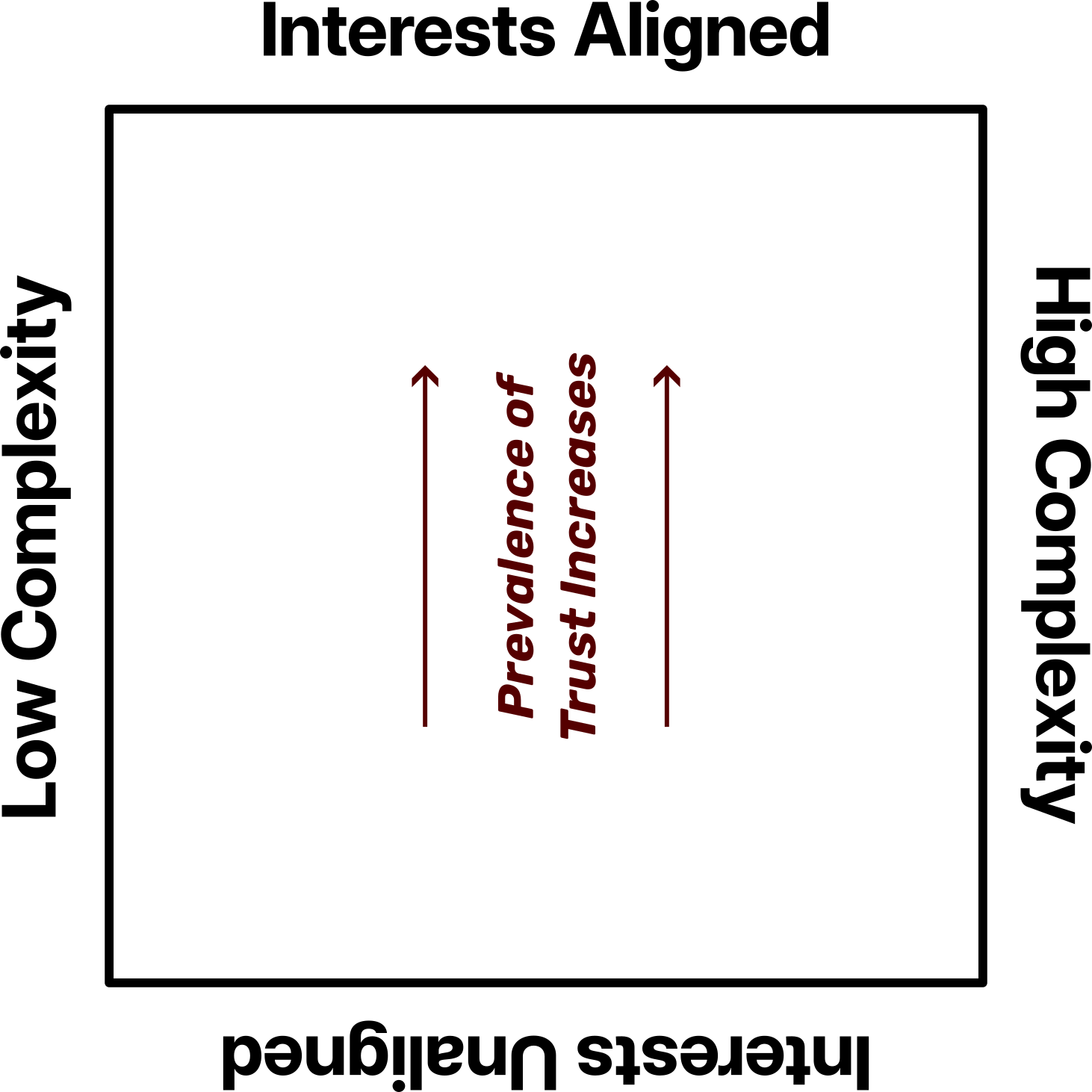

The second dimension also has very clear implications. If group members tend to share the same goal, there will be more trust within the group. If group members have distinct objectives, suspicion and doubt will often affect which decisions are made. These issues can impede free discussions, and thus cause suboptimal decision-making and decrease satisfaction. This dimension, too, is almost obvious: a multitude of objectives decreases the likelihood that any joint decision can satify every member's goal. If we define trust as an expectation about the latter, it becomes clear that unaligned interests do not promote trust.

These two dimensions have important implications for the question of how to structure group decision-making. Various mechanisms, or formats, have different properties that can strengthen the quality of group decision-making in some circumstances and weaken it in others. It is foolish to believe that one mechanism solves all problems. It is important that groups can find ways to implement diverse decision-making formats for diverse problems.

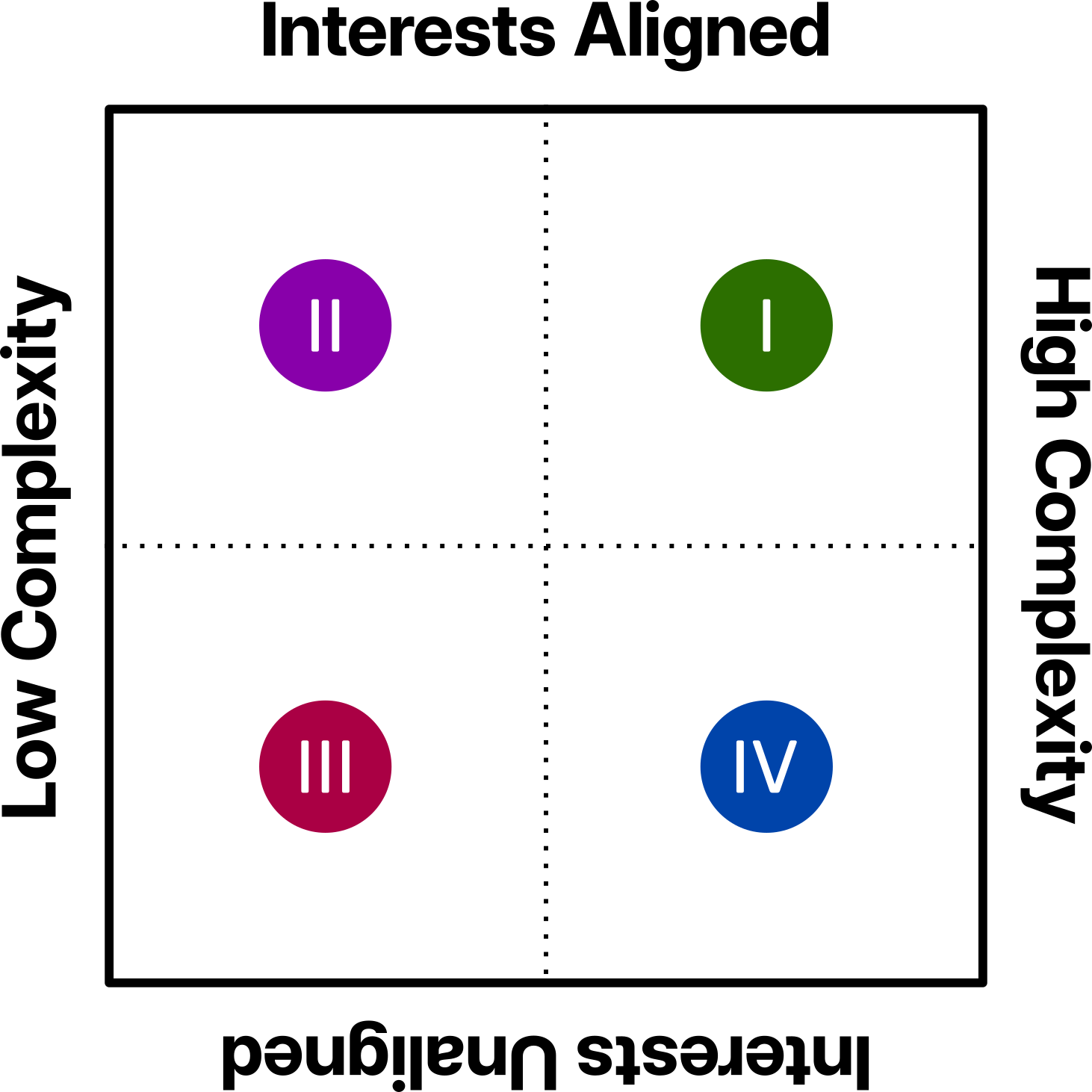

One example is the new revolt against technocracy and “experts” (quadrant I). Experts interface well with highly complex problems under the assumption that objectives are clearly defined and experts can help satisfy these objectives. This example highlights the vertical axis as having a normative character. As I have written before, policy cannot work without values. If people have an objective that conflicts with the stated or implied goal that experts as tasked with reaching (for example: the ascertainment of scientific truth), dissatisfaction is inevitable. If values don't matter, however, delegation to experts or expert bodies can be highly effective. But values often really, really matter, no matter how strongly many try to ignore it.

Another example concerns majority voting. This mechanism is well-known for its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and seeming universal applicability. Nonetheless, the story of the 51 percent oppressing the 49 percent is well-known. Raw majority voting is unable to handle complex scenarios, as evidenced by smart hacks such as logrolling. Moreover, voting works without further assumptions only between two options. If preferences are single-peaked, it also works with more options, but that is unlikely with multidimensional questions. Democracy works best if all citizens share at least some objectives and decisions are simple (quadrant II).

Unanimity can overcome some of these challenges (quadrant III), but it is procedurally tough: it might require substantial “side payments” between players, and is in general highly complex even for simple problems. The great—and obvious—thing about unanimity rules is that they produce a lot of satisfaction (Pareto efficiency) because they avoid the tyranny of the majority. Unfortunately, it is too tedious—where the costs of dissatisfaction are not too high (where there is more alignment of interests), majority rule works better.

The common law is a good example of a mechanism that happens to overcome unaligned interests at high complexity (quadrant IV). In any court of law, interests are inherently opposed. While many matters are simple, there is no limit to the complexity that the common law can handle. The common law is able to do this because it relies on abstract rules that categorically provide solutions for certain classes of problems. One great example of this is the reasonable person standard in negligence law, which provides a consistent framework for determining liability across countless different scenarios by asking what a hypothetical reasonable person would have done in similar circumstances. Since everyone can form their expectations around these solutions, and act accordingly, the common law prevents many issues in the first place, or provides litigants with quasi-dictatorial decision-makers (judge and jury) to settle issues once and for all. While a common law court can in theory settle all problems, it's quite an expensive process, and also probably not fully legitimate from first principles. The former issue is so severe that litigation is often foregone in favor of settlements, i.e., unanimity.

On another note, I have decided to cut back on conference attendance. While I believe that scientific conferences are invaluable for more junior scientists to form connections, I am currently focusing more on improving my research. The problem is that conference audiences often do not have aligned interests, yet are dealing with highly complex issues (quadrant IV). It follows from the discussion above that research simply cannot be improved by fifteen-minute slots with five minutes reserved for “discussion.” To be clear: I cannot really blame the other attendees, as there is just far too much material. (I do blame the organizers, however. Why not leave the afternoons free for scientists to interact?) This is in contrast to more highly self-selected seminars and reading groups, where the material gains focus and there is more space for ideas.

While conferences can be useful in promoting ideas and networking (tasks that have low complexity), they are not made for depth. Ivan Illich was a social critic who frequently met with friends and other discussants. He threw out a provocative idea and then discussed it to the end in all its nuance. Crucially, his audience were people who shared his goal of brutally and utterly dissecting modern institutions. Although I have many differences with Illich, we was able through in-depth discussions to truly get at the bottom of issues. Ivan knew the formats. The goal of research is to find truth, and I no longer believe that conferences are the right tool for that.

For the time being, I will spend my time mostly elsewhere: with other scientists who care, or deeply immersed in my work and that of others.